As COVID-19 hit, Piper and Warren found themselves on the frontlines as essential workers

It’s no secret that COVID-19 disrupted the training schedules of many athletes.

Yet while some athletes were making do with backyard workouts or cross-training, those who doubled as essential workers during the height of social distancing suddenly found themselves balancing long work shifts with sleep, training and proper nutrition. For Jessie Warren and Lilli Piper, it was one of the most unique challenges of their careers.

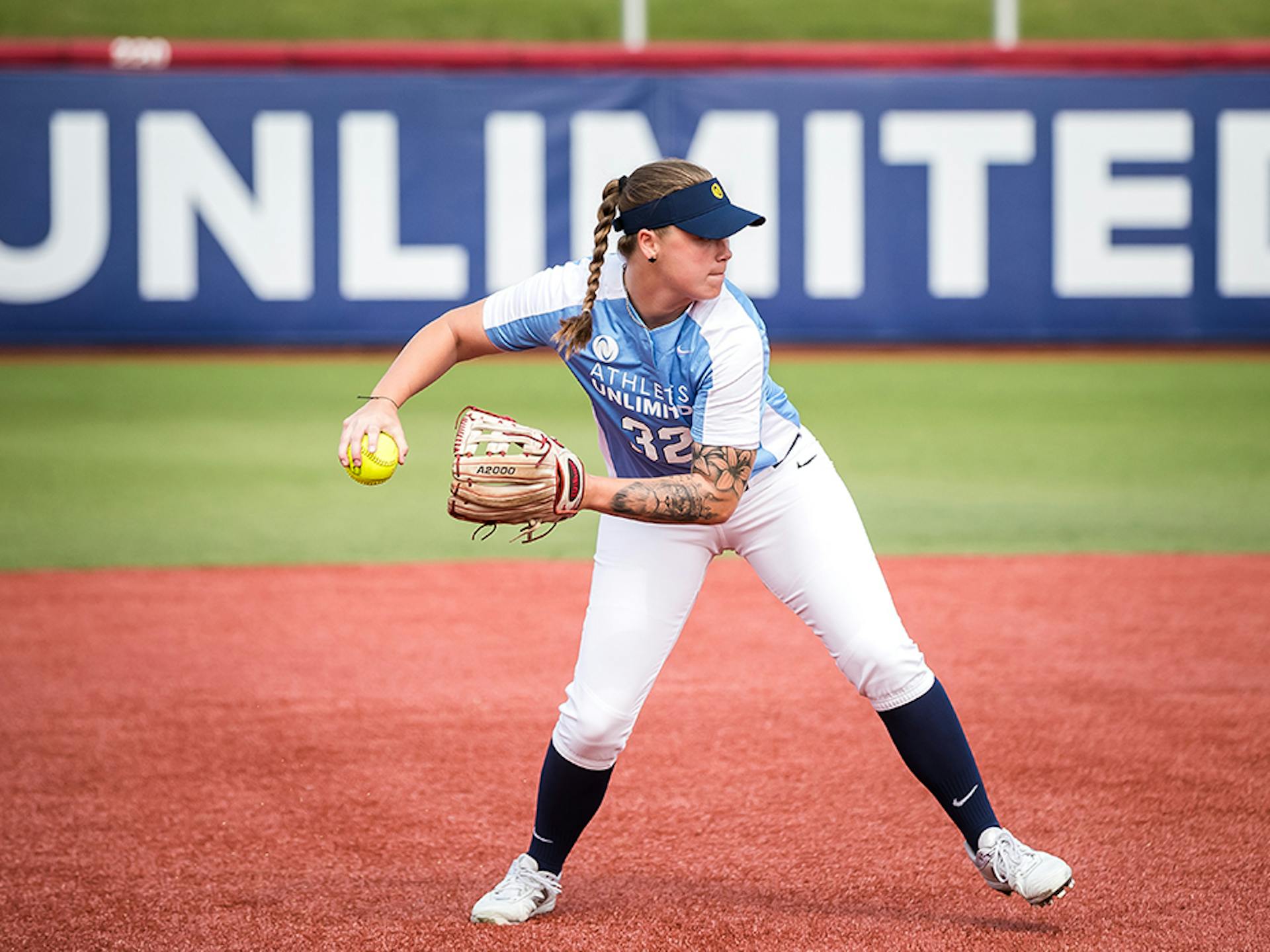

“It was hard,” said Warren, putting it bluntly. When the pandemic began, she had been coaching high school softball. Her life was lined up perfectly to end the season with her team before starting the Athletes Unlimited season. Then, COVID-19 hit.

“When they canceled season I had so much time on my hands and I had to make money in some way,” she said.

She heard from a friend about a titanium plant that was hiring cleaners. Warren signed up for the job.

“I had never really planned to be doing this,” Warren said, but all of a sudden she found herself suited up head-to-toe in personal protective equipment and working the night shift — 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m., just to fill the gap in her finances left by a truncated season.

“At that point there was no training,” she said, noting that the amount of walking she did during her job burned enough calories for the day. When she wasn’t working, she wanted to prioritize sleep — at the end of her 15 or 16 hour shifts she’d already be feeling drowsy. Sometimes she’d nap in her car during her lunch break. Even if she did, usually by the time she got home she barely had the energy to shower before falling into bed, waking only in time to get to work for her next shift.

Despite this chaotic schedule she tried her hardest to stay true to her nutrition plan.

“My timing was backwards,” she said. She’d often refrain from eating during the day — usually she was asleep anyway so this wasn’t hard. Then, she’d eat her breakfast when she woke up in the mid-afternoon.

It wasn’t unusual for her coworkers to see her eating at odd times. “I remember some days I’d be eating spaghetti at 5:00 or 6:00 in the morning, because that was my dinner,” she said.

The potential of contracting the virus was never far from her mind. “It was nerve-wracking going into work,” Warren said, “but I had to, to stay on my feet financially.”

Lilli Piper, who worked in an Amazon warehouse sortation center, faced a similar challenge.

“There were definitely cases in our building,” Piper said. About 500 people worked in her warehouse at the start of the pandemic. Employees would be notified if they were in close contact with someone who had contracted the virus. Piper heard about others receiving a notification, but she never got one herself.

Eventually, as social distancing guidelines became clearer, the warehouse reduced its staff nearly in half — which increased Piper’s workload.

“I think that it was tricky in the fact that we still had to hold up our productivity with less people in the building and farther apart from each other,” she said.

While the effects of the virus are still unknown, the physical toll it takes on athletes wasn’t far from Piper’s mind. “There are symptoms that could affect my ability to play,” she said. Yet she didn’t let the fear of what could happen stop her from doing her job.

“We took a lot of precautions to make sure we followed CDC guidelines so we were pretty good for the most part when we were at work,” Piper said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on all athletes. Even those who weren’t employed as essential workers faced similar challenges with having to detrain, which can cause athletes to lose muscle mass and be more prone to injury if training is restarted too suddenly. Studies show muscle size can decrease between 5% and 10% after 14 to 23 days of detraining.

Without access to their normal facilities and support, athletes can face significant consequences when restarting a training program. NFL players, for example, experienced an unusual break in training during the 2011 NFL lockout, a period of three months. There were more Achilles tendon injuries recorded in the first training camps and start of the season after returning than what was typically experienced in a common season.

Yet for the athletes who double as essential workers, the problem was even more accentuated as training became not just different but temporarily impossible. It’s the type of challenge that Warren hopes is one day avoidable. As both women were driven to the frontlines by finances, Warren sees increased interest in women’s sports, and a better financial outlook for female athletes as part of the solution.

“I just want it to be where everything’s equal,” Warren said. “I just want people to invest in us and know they’re going to get good competition.”

For now, she feels they’re on the right track. “This league is doing an amazing job on that, putting us out to ESPN and all of these brands that are signing with Athletes Unlimited and believing in us and what we’re doing. I think it’s a great start that all of this is happening and I think we’re on a great track to starting equal pay with women and men.”

For her part, Piper isn’t afraid to face the frontlines once again if finances demand.

“When I am done here, I am going to go back to Amazon,” she said. “I am going to continue to work there. It’s just taking the precautions and doing the most you can to make sure you’re safe and the people around you are safe.”