A Q&A with the Athletes Unlimited Data & Scoring Team

You asked, we answered! Our expert team of data analysts and seasoned volleyball professionals are taking on your questions about the Athletes Unlimited volleyball scoring system. Meet the folks behind Athletes Unlimited’s innovative scoring model:

Chris McGown is the Director of Sport for Volleyball at Athletes Unlimited and a consultant coach with USA Women’s Volleyball, the head coach of the USA Collegiate National Team program. He is the president and co-founder of Gold Medal Squared, a worldwide leader in volleyball athlete training and coaching education.

Joe Trinsey is a coach with Athletes Unlimited Volleyball and served on the staff of the USA Women’s Olympics Team (indoors) at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Most recently, he was an assistant coach for the Canadian Women’s National Team.

John Spade is the Chief Technology Officer of Athletes Unlimited and is a patented inventor with over 25 years as a technology professional. His previous work experience includes serving as the CIO of the NHL Florida Panthers and the SVP of Technology at Intelepeer.

Soham Mahabaleshwarkar is a Data Science intern at Athletes Unlimited and a graduate student at New York University pursuing a Masters in Computer Science specializing in Data Analytics, having previously completed his undergraduate degree in Computer Engineering from the University of Pune. He is the co-founder and CEO of Scriblr, a literature tech company he founded in 2019 aiming to change the way readers and writers both create and consume books.

How different is the format going to be from international volleyball?

McGown: We wanted to keep the set format that was more familiar to not only our athletes but to our fans. So the two primary drivers were: How do we help manage athlete load; and from a scoring system perspective, how do we create an equal number of opportunities to score points every time you go out and play? In fixing the match to three sets, it accomplished both of those things: number one is that it gave us this window that we felt was manageable in terms of athlete load; and it keeps the amount of points that could be scored by an athlete roughly equal from match to match. In international volleyball, teams play best of five, which creates a more difficult load for the athletes and makes scoring opportunities unpredictable. You can learn more about how we arrived at a fixed-set format here.

How will substitutions work?

McGown: When we started thinking about subs, there were two things: number one, we wanted to keep the game of volleyball as true to an FIVB format as we could. In those competitions, there are six total subs in a set. The other thing that we wanted to do was allow teams a little more flexibility in using those subs. So, you get six subs in a set, but unlimited entries. That created a little bit more flexibility in how bench players could be used and how you might strategize within the set, but it still kept things reasonable so that you couldn’t go back to what it would look like to play NCAA or club volleyball.

This is one area that I think we might be pioneering some things; I think the FIVB has talked about unlimited entries with a limited number of subs for a while, and this might be something where they’re watching us closely to see how it goes.

Why is the draft different from the softball season? Why does the fourth ranked player get the first pick?

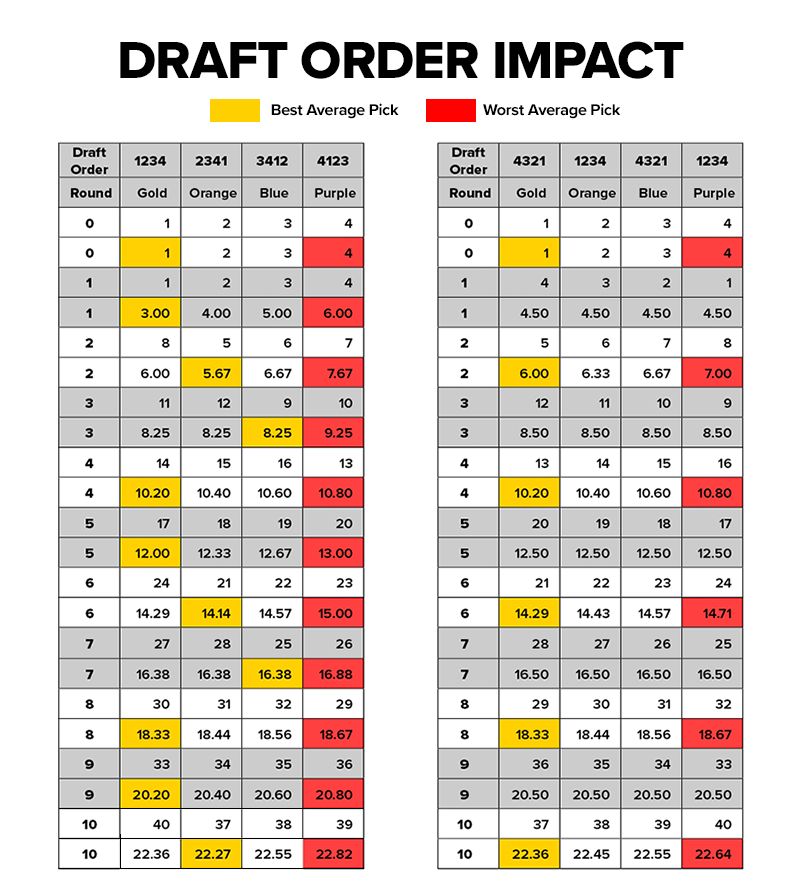

Spade: When we created the draft order for the softball season, we weighed a number of different options and actually found that giving the fourth-ranked player the first pick was the most equitable option. At the same time, we also felt that earning the top spot on the leaderboard should be worth something, namely the first pick of the draft. So we went with the next best option, a rotating draft order in which each captain gets the first pick of the round in chronological order (i.e. 1234 -> 2341 -> 3412 -> 4123…).

When we watched the softball season play out and revisited the discussion, we learned a couple of things. Number one is that captains actually preferred to be ranked second or third, as they were able to make strong picks with less waiting time in between (for example, the second ranked player gets the 2nd and 5th pick). Number two is that giving the first pick to the top player on the leaderboard was more likely to ensure that her team remained dominant over the course of the season, which isn’t an equitable outcome.

We went back and created analyses for a variety of draft orders and essentially pitched them to the Volleyball Player Executive Committee, and they agreed to give the first pick to the fourth-ranked player as a gesture towards equity. In addition, the snake-like order of the draft still gives the top-ranked player the fourth and fifth picks consecutively, which isn’t a bad position to be in.

If positions perform different skills more or less often, how do you make sure that everyone has a shot at winning the league?

McGown: The single biggest challenge we faced was this idea of, as Joe Trinsey calls it, “usage”. As we know, in volleyball, not everybody attacks, and not everybody attacks as much as everybody else by position. Middles are going to get less volume than outsides and opposites, middles don’t pass, setters don’t pass, opposites don’t pass… So how do you try to create a scoring system that accounts for this disparity in usage?

The idea was, essentially, that we’re going to score points for positive performances, and you could conceivably lose points for negative performances. So, what we see is the outsides are going to get to attack a lot, but there’s also, with the opportunity to score points by attacking, there’s also the opportunity to get penalized for errors. If you play great, if you excel, if your team does great, you can end up in the top ten no matter what position you’re on. You can read more about how we resolved usage discrepancies here.

Will athletes act differently knowing that they can earn individual points?

Trinsey: We hope not! The foundation of the scoring system was to reflect how much each action affects winning and losing a point. But in some cases, the knowledge of that, or the question about how certain actions would be scored, created the possibility to affect play. We wanted to avoid that as much as possible.

The biggest example of this was our decision to exclude any penalty for digging errors. There’s a good argument to be made that, if I make 10 digs and only 12 balls were hit my way the whole match, I deserve more points than somebody who made 10 digs but had 20 opportunities.

However, this starts to get very subjective. Where does a “digging error” end and an “undiggable ball” begin? We didn’t want players to start shying away from dig attempts if they thought they would be penalized for a digging mistake. You can check out this blog post to learn more about how we developed our individual scoring system.

Why is it that skills like assists and passes are so low-scoring when the penalty for performing them poorly is so great?

Trinsey: Because professional players are so good at them! In FIVB volleyball, the average passer will pass more than 7 good passes for every time they are aced. So on 100 total passes, you might expect about 50 good passes and 7 times aced, for a total score of +16. Liberos will likely be quite a bit better than that, while some offensively-minded outside hitters might struggle to stay in the positive.

But that’s part of the reason why there has to be a penalty for getting aced. Teams often try to serve the weakest passer and avoid the libero. So despite the fact that the libero is usually the team’s best passer, in professional volleyball, they only lead the team in total good passes about half the time. So a big part of a libero’s value is not only what she does (make good passes) but also what she doesn’t do (get aced) and we wanted the scoring to reflect that.

Setters are much the same way in that professional setters will compile 30-40 assists for every setting error they make and top setters make fewer errors than average setters. It sounds counter-intuitive, but if you’re the best setter in the league, you want a penalty for setting errors, because that differentiates you from your competitors.

If you can predict that a certain situation within a rally gives a team a certain percentage chance of winning the rally, how does that impact how you train and strategize?

Trinsey: My perspective is that if you have good analytics, 90% of what they tell you will seem like simple common sense. Passing in-system increases your odds of winning the rally. Isolating a hitter against one blocker improves her hitting efficiency. And so on.

The value of analytics comes in that last 10% that might be either (1) counter-intuitive or (2) give insight into matters of degree. Most top coaches and players have learned this intuitively through experience, and analytics just adds to that knowledge.

For example, digging a hard-drive spike perfectly would be great, but the odds of winning the rally don’t go down that much (“matter of degree” from above) if you dig 10 or 15 feet off the net. So that lends to the idea of not trying for perfection on hard-driven spikes and just aiming to, “keep it on our side.” Most players who get to a high level figure this out intuitively, and analytics are there to supplement that intuitive knowledge.

At the end of the day, simulations will never be as accurate as actual historical data. How will Athletes Unlimited revisit the scoring system after the volleyball season is over?

Mahabaleshwarkar: I think the first thing to realize is that it’s extremely unlikely that a significant statistical trend can be found based on data from one season (~15 games). We’d definitely need a much larger sample size to extrapolate trends and figure out if we need to make changes to the system. However, based on the results we see from the season, it is extremely likely that we’d be able to better understand the foundations of the system and the points more and how they correlate to making winning plays in volleyball. We’d get a better feel for the expected value of points earned by a player per game, which, in turn, would impact how we approach team win points and MVP points.

I think we’d also be able to understand the dynamics of which plays in the game make for greater impact on the end result. Based on the balance of the team and player standings, as well as the eye test, we’d be able to change up the structure of how we award points for certain plays: maybe digs go up a point, or negative points go up across the board based on what we see from the players. I think the goal is always to build a league with excellent play and competitive parity from the top to the bottom of the playing field, and with this first season with an all new scoring model for volleyball, we’re just getting started with understanding what works and what doesn’t to keep the audience engaged.

Hungry for more? Check out our scoring system white paper, authored by this very same team of seasoned experts.